The previous chapters talked about training, which allows you to get some data about the feelings of bees. The prerequisite for such experiments is that the bees we want to train come to our experimental table. To attract bees to the experimental table, we put on it several sheets of paper, richly oiled with honey. In most cases, it takes several hours, and often several days, until one of the scouts scurrying around in search of food will happen to be nearby and, attracted by the smell of honey, will begin to recruit it.

Now we can consider the game won and start preparing for experiments with the certainty that in a few minutes, beside this bee, our table will have dozens and even hundreds of bees. If we trace where these bees come from, it turns out that all of them, almost without exception, belong to the same family as the first beekeeper who discovered the source of the bribe. So, it seems that the bee somehow reported at home, in the hive, about a rich find and led to it other bees.

We would very much like to know how she did it. To find out, there is only one way: to see what the bee does and how other bees behave towards it. In a normal beehive, you will not see this, you will have to use an observation beehive.

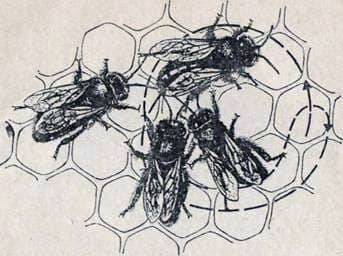

We will place next to the hive a feeding trough. Let’s mark the first bee on it, so that later it could be recognized among other bees in the beehive and not lose sight of. Here she enters the chute, runs up the honeycomb and then finds herself somewhere among her hive girlfriends. It burdens the honey collected from it, emerging from its mouth, in the form of a shiny drop, which is immediately absorbed by two or three of its girlfriends, stretching her proboscis to her.

Fig. 74. Returning home collector (in the picture on the left below) gives nectar to three other bees.

They take care of its further use and, depending on the circumstances, either feed their hungry fellow citizens, or fill with honey cells, in a word – are engaged in internal affairs, which the assembler herself does not delve into.

Meanwhile, on the honeycomb, a performance is played, worthy of the pen of glorified bees of great poets. But they still did not know it, and therefore the reader will have to be content with his prose description.

Circular dance as a means of mutual understanding.

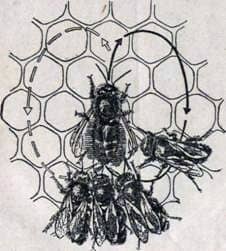

Having freed from the load, the picker starts a kind of circular dance. She runs fast, stepping steps to the place of the honeycomb where she was just now, swiftly turning either to the right or to the left, and, constantly changing this direction, describes one or two circles.

This dance takes place in the very midst of bees and is especially noteworthy and interesting in that the bees surrounding the dancer are also involved. Those of them who are closest to the dancer, follow her and, stretching out their tendrils, try to touch them with her abdomen. They repeat all the turns of the dancer, so that in her swift movements she drags a whole tail of the other bees behind her.

Fig. 75. The circular dance of nectar gatherer on a honeycomb. The dancer is followed by three bees behind her, who receive information.

This spinning can last for several seconds, half a minute or a full minute. Then the dancer suddenly stops it, is released from the retinue, often another or third place of the honeycomb regurgitates a drop of honey – and again begins the same dance. Having finished it, she hurries to the tap and again flies to the trough to bring a new burden. At each return home, the presentation on the cells repeats itself.

Under normal conditions, the bee dances in the darkness of the bee hive. Consequently, her friends can not see the dancer by the hive. And if they can notice her movements and repeat all the turns behind her, they are guided only by their tactile and olfactory perceptions.

What should this circular dance mean? Obviously, he strongly excites the beehive nearest to the dancer. Watching closely this or that bee from the suite of the dancer, you can see how she begins to prepare for the flight, lightly cleaned, and then makes her way to the tap and leaves the hive. After a while after the first bee, new bees appear on the feeder. Returning home loaded, they also dance, and the more dancers, the more beginners arrive at the place of feeding. There is no doubt that there is a correlation between these phenomena. The dance in the hive notifies the bees that a rich bribe has been discovered. But how do the bees find the place where they should go after him?

First of all, the suggestion suggests that bees after the end of the dance rush to go with the dancer and fly after her, when she again goes to the source of food. However, careful research shows that this is not entirely true. Beginners, apparently, do not know where the purpose of their search is. The symbolic gestures of circular dance tell them only that the source of food should be searched around the hive, and that’s what they do. You can verify this with a simple experience. Feed a small group of tagged bees on a table, standing about 10 meters to the south of the hive. Then, a little further from the hive in the south, west, north and east directions, we will arrange the feeding troughs in the grass. A few minutes after the pickers, returning from the southern feeder, began to dance, beginners from our hive appear on all the feeders.

If you hide food from the bees that gather it, they will behave exactly as if a natural bribe was interrupted due to unfavorable weather and the most ordinary flowers stopped allocating nectar: the bees stay at home, the dances cease. Feeders around the hive with honey can now stand for hours and even days in the grass, not detectable by any bee.

This may seem strange, because a small number of bees, marked on the trough, are not the only family gatherers. While they were flying to a cup of sugar syrup, hundreds and thousands of their friends visited various flowers, collecting pollen and nectar from them. When we stop feeding the bees on an artificial feeder, the remaining bees continue to collect the nectar. Why, after returning from a flower bribe, they do not send their friends to search for him in all directions, and also to the trough with the help of dance? This can be answered: Of course, they sent other bees if they found a rich source of a bribe, but not to a cup of sugar syrup, but to those flowers that they themselves successfully used.

The biological significance of the floral odor, considered from a new perspective.

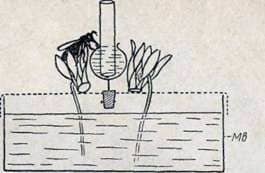

Not a glass cup, but flowers – natural vessels with food for bees. We act in accordance with nature, if we choose a small bouquet of flowers, for example Alpine violets, instead of a glass cup filled with syrup at the meal site we have chosen. In order to be able to use any flowers and not depend on the amount of nectar they are given at the moment, we will apply a drop of syrup to each flower, which we will replenish as we select it with bees. To bees found food in flowers and could not collect from the table accidentally dropped on it drops, put a vase of flowers in a large dish filled with water. Marked bees, who found a rich bribe in alpine violets, dance on the combs.

Fig. 76. Alpine violets as a feeder for a group of tagged bees.

Put somewhere in the grass in a cup of alpine violets, which are not sprayed with sugar syrup, and next – a cup with other flowers, for example with phlox.

Figure 77. A cup with alpine violets and a cup with phlox on a meadow near the feeder shown in Fig. 76 New arrivals are only interested in Alpine violets.

The signal of the dancers works flawlessly, and soon bees appear everywhere, rushing about in search of the whole meadow. They fly up to the cups of flowers, fall on the Alpine violets and stubbornly swarm in them, as if not doubting that here they will find something suitable. But they pass by the cup with the phlox, without showing any interest to them.

Fig. 78. Feeding of labeled bees on flowers of phlox.

Now remove the alpine violets from the feeding spot and replace them with phloxes, which in the same way are abundantly sprinkled with sugar syrup. Gatherers are the same bees as before, but they take bribes no longer from Alpine violets, but from flox flowers. Everything remains the same in the meadow. But in a few minutes the picture changes.

Interest in alpine violets weakens, newly arrived bees only fly to phlox, moreover, everywhere in neighboring gardens where there are only phloxes, we see bees zealously visiting their flowers – a curious sight for everyone who knows that the deep corolla tubes of this plants are only accessible to the long trunk of butterflies and that the bees are completely unable to reach the nectar hidden in their depths. That’s why they are usually never seen on phlox. It is quite obvious that the dancers who seek bribes reported that they need to look for what kinds of flowers give a rich bribe! The success of this experiment does not depend on whether we use the flowers of the alpine violet or phlox, gentian or wiki, thistle or buttercup, beans or immortals as a source of food.

The expediency of such behavior of bees becomes obvious, as soon as we imagine natural conditions. If the intelligence bees find any flowering plants, they report their findings, dancing in the hive. The bees mobilized by them are directed to that kind of flowers, which are abundantly nourished by dancing, and do not waste time looking for useless flowers without nectar. Is all this clear? After all, it is impossible to admit that in the language of bees there were names of all kinds of flowers.

And yet it is so. “The language of flowers” is revealed here surprisingly simply, expediently and admirably. At the time when the picker sucks out the sweet juice from the flower, her body is soaked with its fragrance. Returning home, she still smells like the fragrance of these flowers when she’s dizzy. Her hive friends, following her and so lively exploring her mustache (olfactory organs), during the dance perceive this smell, capture it in memory and. They are guided by it when they search for bribes, examining the surrounding terrain.

If instead of flowers to use essential oils or artificial aromatic substances, the connection existing between the bees and the odor becomes even more obvious. We will feed the labeled bees with a syrup from a glass cup, which stands on a stand that has the smell of mint. Excited by dancing, the newcomers flying out of the hive curl around all objects that come to their eyes, which have received this smell after applying a small amount of mint oil to them. They do not pay attention to other smells. But it is only necessary to change the aromatic substance applied to the stand, as with the change in the proposed odor, the purpose of the bee searches will change.

However, the initial version of the experiment, which we take as the original one, provides for the bees to be fed on a cup without a smell. In this case, the dancer’s suite can not detect any specific smell emanating from it. But even now they fly out of the hive, knowing that all the scented flowers that meet on their way, do not deserve attention and there is no need to waste time visiting them.

Botanists of the past centuries have seen in the smell of flowers only a means to attract insects looking for food. But for bees, the smell, moreover, serves as an identification mark, allowing them to identify with certainty the flowers they have already visited, from others that have a similar color. This ability of bees is a necessary prerequisite for their flower permanence. However, the meaning of the smell is not only this. Like the precise expressions of a verbal language, a specific smell brought home a simple and clear message to the bees in the beehive of the purpose of their search flights, to which they are inspired by the dance.

As the bees bring home the smell of flowers.

Not very attentive observer is inclined to believe that many flowers do not smell. Even from a distance there is a striking bright color of the yellow buttercup, blue fins, red beans, but the bouquets of these flowers do not fill the room with fragrance. And yet, one whose smell is not dulled by excessive smoking, can detect a tender smell peculiar to each species. For this it is enough to collect a dozen such flowers together and bring them to the nose.

Among insect pollinated plants, rare exceptions are those whose flowers are completely devoid of odor. These include lingonberries and wild grapes. Indeed, when mobilizing these bees in a beehive, as expected, there is no idea of the purpose of the search flight. It is surprising only that even the weakest, hardly appreciable for us a flower smell is enough, that bees in a hive could learn, whence the dancer has arrived. How does the dancer manage to bring home the delicate scent of flowers she visited?

Part of this can be explained by the fact that aromatic substances are retained on the bee’s body better than, for example, on glass, metal, paper, cotton wool or even on the body of other insects. A person can check this with his own sense of smell. This can be shown even more clearly if the bees are inspected for some floral scent, and then they are offered a choice of beside the bodies of bees and other objects that are soaked with a floral odor in closed vessels and after that they are ventilated for a while. On no other object is it possible to recognize the odor for so long and none of them are so persistently visited by trained bees, like the body of a bee. Its outer cover, apparently is adapted by nature to absorb the aromas of flowers.

But to said it is necessary to add that the nectar, which stands out at the base of the flower, is stored in its fragrant calyx and therefore acquires a specific smell of the flower. The collector who took it carries a scent sample with her nectar, with which she introduces other bees, feeding them a drop of nectar. Among these bees there are some who follow her when they dance and, after receiving a fragrant password from her mouth, fly out in search.

Fig. 79. Through a narrow crevice, the bee collects a syrup with a smell of phlox in the honey zobik, while its body is soaked with the smell of cyclamen. Mv – a bowl of water, covered with a mesh.

It would be very interesting to know which smell is more effective – the one that is “perfumed” by the bee, or brought in honey cinders? This can be known if you put both smells in the conditions of the competition. We put on the flowers of phlox drops of sugar syrup and leave them for about an hour so that they are soaked with the smell of the flower. Then we will allow several bees on the cyclamen flowers to take a sugar syrup from the bottle with the smell of phlox through a narrow slit. During the dance at home, the smell of cyclamen will come from their outer cover, and the smell of phlox from the syrup they give out.

To see the result, we will observe behind the cups with flowers of phlox and cyclamen, placed in the grass near the feeder. Both cups are visited by beginners. But the smell brought in zobics wins the competition in the event that the source of feed is at a considerable distance from the hive.

The experiment was repeated under conditions where the distance between the feeding area and the hive was 600 meters. In long-distance flights, the bee’s body is ventilated more strongly and the odor retained by the outer cover significantly loses its intensity. That is why the mobilized beginners are guided in their search almost exclusively by the floral smell of nectar delivered in honey cinders.

Thus, we learn what biological significance is the nectar, perceived by the smell of flowers, delivered by bees home in honey cinders, as in well-corked bottles.

Regulation of supply and demand.

Dances of bees acquire their full biological meaning only under such circumstances, when they arise under the influence of a copious bribe. With a weak bribe, a large mobilization is unprofitable for the family and dances does not happen.

If you cut several flowering branches, for example acacia, put them in a vessel with water and protect from insects, then for several hours in the flowers will accumulate a lot of nectar. Now we will offer this bouquet to a group of bees, who before that flew for sugar syrup to the feeder. It will take a little trick to make them, without losing time, switch to visiting a new feed source for them. As soon as this happens, they will start using a natural rich source of bribes and will quickly receive reinforcement as a result of mobilization dances.

But soon bees will become so much that they gather faster and take away the nectar, than it again accumulates in the flower cups. Because of the excess of bees, bribes become more scarce. And, although the collection continues with unflagging persistence, the dances cease and a group of bee pickers do not receive a new replenishment from their native hive.

Along with the amount of “sweetness” of the secreted nectar is also crucial for the productivity of a bribe. If you add one piece of sugar after another in a glass of water, then eventually the sugar will cease to dissolve, even with prolonged stirring and in the form of a sludge, it will sink to the bottom of the glass. Such a thick, “saturated” sugar solution contains as much sweet substance as water can generally take. The nectar of some flowers is just such a saturated solution. In this case, of course, it is worthwhile to recruit as much as possible – how much can go into zobics – and mobilize all the forces of the family for this work.

In the flowers of other plants at the same time, a liquid, low-sugar nectar is formed. With an equal amount of liquid in the cinders, bees deliver much less sugar home. Mobilizing pickers to use this find is as vigorous as in the first case, inexpedient, and in reality this does not happen. In order for the dances of bees to be brisk and prolonged, the sugar solution should not only stand out in abundance, but also be very sweet. The less he is sweet, the more dull the dancing will be, and the weaker the dance, the less his recruiting power. If the sugar content in nectar falls to a certain level, dances will stop even if nectar is released in abundance.

In such a simple way, the mobilization of bees-pickers is regulated depending on the productivity of the source of the bribe.

With the simultaneous flowering of many plant species, the ones most visited are those whose flowers produce more sweet nectar than others. Bees searching for such flowers dance more vividly than those who at the same time discovered less rich sources of bribes.

Specific smell, brought home bee-dancers, determines the correct choice of the degree of mobilization of the family. With extreme clarity, for example, it is made clear that today, judging by the smell, most of all nectar will be obtained in the flowers of plums. Thus, in the honey storeroom of bees, a nectarean stream is pouring in mainly from the source most deserving of attention at a given time. Simultaneously, the flowers that produce the most sweet nectar are best visited by bees, and thus provide themselves with the best pollination and the most complete tying of seeds.

“Flask with spirits” on the body of a bee.

Fig. 80. Three bees at the feeding trough: the bee to the left stuck out the fragrant gland, which in the form of a narrow shiny ridge is visible near the tip of the abdomen (indicated by a cross). At the right bee the fragrant gland is closed.

Each worker bee carries a ready-to-eat “bottle of perfume,” in other words, a small perfumery factory. It is located near the tip of the abdomen, in the skin fold, which is usually curved inward and therefore not visible, but can be arbitrarily protruded in the form of a wet glossy roller. Then in the air, an odoriferous substance spreads out by the tiny glands located in this skin pocket. Its aroma, reminiscent of the smell of lemon balm, is felt for us; for bees it is more intense and is perceived for a few meters as an attracting smell.

We have already talked about how, with the “wagging tail” with the help of this smell, some bees point to others the way to the tap. Collectors use a fragrant organ also when visiting flowers, if the bribes are good enough and it is desirable to attract new auxiliary forces to it. Highlighting the attracting smell, the bees help to find a target for their girlfriends, whom they raised in alarm by dancing and forced to fly out of the hive.

It is not difficult to verify this with the help of the corresponding experiment. We’ll put two cups with sugar syrup near the observation beehive and on each of them let us gather for ten bees. They come from the same hive, but each group “knows” only their own cup.

Let’s now offer a “good bribe” (sugar syrup in abundance) on one cup, on the other – a “scant bribe” (a blotting paper moistened with sugar syrup so that it can only be collected with difficulty). Collectors who use rich bribes, dance, others do not. To the first group for one and the same time, ten times more beginners join than the second. And this is very advisable. How does this happen? Bees that are on a honeycomb can not know where the dancers came from, because no one of these two feeders was given a floral scent. They search the area without having a specific purpose. But if they approach the rich source of food, then they will attract attracting the smell of previously gathered collectors; at the same time, they often fly past the trough, poorly stocked with syrup,

What is really so, shows the control experience: you can, as it were, plug a bee-bottle with perfume, pasting the dermal sac in which it is, with a thin layer of shellac film. Now the bees will not be able to open the fragrant crease. This does not interfere with bees-gatherers in their work. They do not even notice it, and they dance as animatedly with a rich bribe as before.

We will present this time two cups filled with sugar syrup. Both groups of bees dance enthusiastically. But that group of bees that can not produce an attractive odor receive a replenishment amounting to only a tenth of the replenishment of the second group.

The same role as in the feeding troughs, the fragrant organ plays and when flowers are visited by bees.

Wagging dance tells the distance to the source of food.

For many years, experiments with the feeder were conducted only in the immediate vicinity of the hive. In the area of the hive beginners quickly oriented and were numerous. If the control cups were exposed at a greater distance, while the feeder remained near the hive, the newcomers arrived at the cups the later and in the smaller number, the greater the distance. This was not surprising. It is quite clear that the mobilized bees primarily look for food near the hive and, only if they do not find anything here, the radius of their flights increases more and more.

But one day, when the feeder was installed at a distance of several hundred meters from the hive, only a few newcomers were looking for it near the hive, while the area of the far-away feeder was flown by a significant group of bees. This aroused the suspicion that the dance also indicates how far to fly.

If we organize the experiment so that the numbered bees from the observation hive gather food near it and at the same time other labeled bees from the same family – on a remote feeder, then on the honeycombs we will see a striking picture: all the bees visiting the feeding troughs. located near the hive, dance a circular dance, and bees, arriving from distant feeders, dance wagging dance. In this case, the bee runs a certain distance along the straight line, returns, makes a semicircle to the starting point, again runs along a straight line and describes the semicircle in the opposite direction. Such a dance can last several minutes at the same place.

Fig. 81. The wagging dance.

This dance differs markedly from the circular by the rapid wagging movements of the abdomen, which are produced just during the rectilinear run (wagging run). At the same time, the dancer publishes a rustle, perceived even by a person, if one end of a plastic stethoscope is inserted into the ear, and the other end is brought to a dancing bee.

Fig. 82. Vibrational movements during the wagging run, recorded acoustically.

The sounds produced can be registered with a microphone. The oscillations will not be reproduced as a long, prolonged tone, but as repeated very short vibrational tremors.

Each individual vibration thrust lasts an insignificant fraction of a second (15/1000 seconds), the same short pause separates it from the next. The oscillation frequency of an individual tone is approximately 250 hertz and corresponds to the oscillation frequency of the wings. Consequently, these whistling rustles are produced by the pectoral musculature of the wings, without being accompanied by real blows of the wings.

Fig. 83. Electromagnetic recording of wobbling movements with vibration movements superimposed on them. The wobbling motions shown in Fig. b reproduced in enlarged form. (According to G. Esh.)

Approximately 30 seconds of such vibrations follow one after another in a second. This frequency is perceived by our hearing as a raspy noise.

With the help of a miniature magnet dancer stuck to the dorsal part of the abdomen, these vibrations can be recorded on an electromagnetic film, and the wobbling movements of the abdomen are recorded with them. It can be seen that short vibrational jerks, regardless of wagging motions, overlap them, that is, they are not associated with a certain phase of wagging motion.

However, the duration of the sound exactly corresponds to the duration of the wagging run, therefore, this run is “emphasized” not only by the wobbling movement, but also by the sound emitted simultaneously. It has already been mentioned that bees, although not “hearing” the vibrations transmitted through the air, are very sensitive to the vibration of the substance on which they are. Therefore, they can perceive the creaky noise of a dancer, following her on a honeycomb. Wagging dance, and especially the phase of rectilinear run, is followed with great attention by the bees following the dancer.

If the feeding trough near the hive is rearranged gradually farther and farther, when the distance reaches 50-100 meters, the circular dances of the pickers go to wagging ones. When the trough is between 100 and 50 meters, the wagging dances are replaced by circular dances. Circular and wagging dances are different expressions of the bee language, informing whether the source of the bribe is close or far away. It is in this sense that they are understood by bees in the hive.

Only by indicating “closer than 100 meters” or “farther than 100 meters” to bees that must fly out and find the source of food, would be rendered a weak help, since the zone of their summer extends for many kilometers in all directions from the native hive. With the gradual movement of the trough to the border of their flight zone, a regular change in wagging dance is revealed, allowing the bees and the researcher watching them to obtain a more accurate idea of the distance to the source of the bribe. At a distance of 100 meters, the dances become swift and turns (see Figure 81) quickly follow one another. The more significant the distance, the more moderate the tempo of the dance, the slower the turns follow, the more stable and longer the straight wagging run.

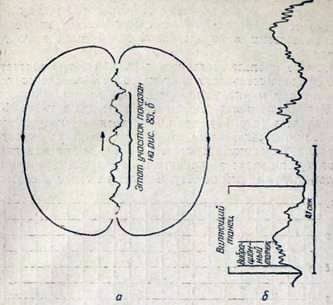

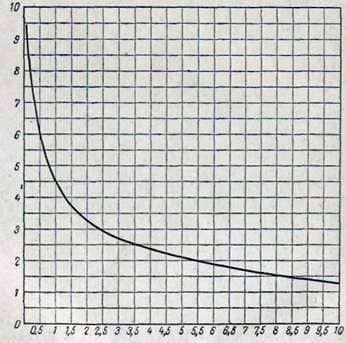

Fig. 84. The curve clearly shows how the tempo of the dance slows down with increasing distance. Left: the number of wagging runs in 1/4 minutes; below: the distance from the hive to the feeder in kilometers.

With the help of the clock it can be established that when the feeder is removed by 100 meters, the bee makes about a quarter of a minute about nine to ten straight runs during the dance, at a distance of 500 meters – about six runs, at distances of 1000 meters – from four to five runs, 5000 meters – two runs and 10 000 meters – on average a little more than one run.

On such remote sites, the bees fly only if they are very attracted there and if closer to the smile they can not find anything more significant.

Numerous observations show that the signal related to distance is related to the duration of the wobbling run, the “wobble time”, which is so emphatically emphasized by wagging, movements and produced sound. Bees should have a subtle sense of time, thanks to which the dancer, moving in the appropriate rhythm, is able to inform her friends so that they can correctly understand and evaluate this information.

Is she really capable of this? How accurate are the newcomers flying out of the hive, the distance indicated by the wagging dance? To find out, at a certain distance from the hive we will feed several numbered bees with sugar syrup, setting the feeder on a stand with a faint smell of lavender. We will decompose the same fragrant bait, but only without food, at different distances from the hive.

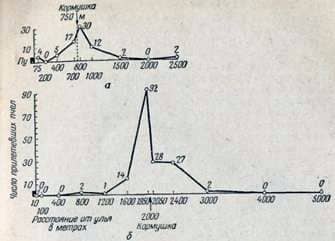

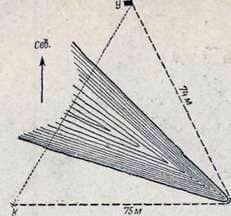

Bees pickers dance on the combs and send their friends to find a “restaurant” that smells of lavender. In one such experiment, the feeder was installed 750 meters from the hive, and the flavored plates were spread in the same direction at a distance of 75, 200, 400, 700, 800, 1000, 1500, 2000 and 2500 meters from the hive. Near each of them was an observer who registered within 1.5 hours each arriving bee.

Fig. 85. The result of two “step-by-step experiments”. In the first experiment (a) the trough with several numbered bees was 750 m from the hive, in the second experiment (b) – 2 km. The curves show the number of newcomers who appeared on the corresponding observation posts.

In Fig. 85, and the number of newcomers who appeared on different plates is given, and the drawn curve makes the result of the experiment more vivid. In another experiment, the feeder was placed at a distance of 10, 100, 400, 800, 1200, 1600, 1950, 2050, 2400, 3000, 4000 and 5000 meters from the hive. Over the expectation, the mobilized bees strictly followed the instructions of the dance, and spent hours searching the area where the feeding trough was located.

But how can bees know how far they need to fly? Observations made in windy weather give some idea of their method of measuring distance. If you fly to the bird feeder against the wind, then when you return home, they show a greater distance in the dance than in the windless weather, and with a favorable wind – less.

If in windless weather they have to fly to the place of collection of a bribe abruptly uphill, then this affects the dances just like the lengthening of the distance, and the flight downwards – as its reduction. Probably, the measure of determining the distance is the energy expended on the flight to the source of the bribe.

Wagging dance indicates to bees as well the direction to the source of the bribe.

The bee family would have received little benefit when it learned that 2 km from the hive the lime blooms, if at the same time there were no instructions on the direction in which it should be sought. The wagging dance also contains such a message. It lies in the figure of the dance, namely in the direction of the straight waggling run.

By reporting the direction, the bees are used in two different ways, depending on whether they dance, as usual, on the vertical surface of the honeycomb in a hive or on some horizontal surface, for example on a landing board. The direction on a horizontal surface should be considered as a historically older form. And since it is also more understandable, we will begin with it.

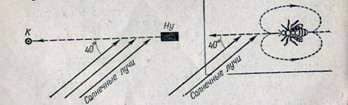

Remember that the sun is used as a compass.

If during the flight from the hive to the feeder the sun was from the picker, for example, in front to the left at an angle of 40 њ, then, returning to the hive, it sticks to the same angle in relation to the sun in a straight wagging run and points directly to the feeder. Seeding bees behind her pay attention to the position that she takes in relation to the sun during the wagging run. Thanks to this, when flying out of the hive, they take the same position as the picker, and choose the right direction to the source of the feed.

Figure: 86. Specifying the direction of the sun when dancing on a horizontal surface. Left: Well – the observation beehive; л – feeding trough; —- direction of flight to the place of bribe. Right: wagging dance on a horizontal surface.

But this happens only when the dancer sees the sun, or at least the blue sky, dancing, for example, on a landing board, which is often in warm weather, when the receptionists meet returning gatherers at the entrance to the hive. You can also remove one honeycomb from the hive and hold it in a horizontal position under the open sky.

Dancing bees are not so easily confused. They point the direction to the direction of the world where bribes were taken, and if you rotate the lying honeycomb like a turning circle on a railway, then, by allowing the dance floor to rotate beneath their feet, like the compass needle, continue to indicate the desired direction. But, if only the sky is closed from their eyes, complete disorientation will ensue and confusion will begin in the dances.

Inside the hive is dark, the sky is not visible, and the honeycombs are located vertically. All this does not allow us to indicate the direction in the way we have just met. Under these circumstances, bees use a second, even more remarkable way. Taking as a basis the angle between the direction in which they flew to the trough, and the straight line to the sun, they keep it in the dance, using as one of the components the direction of gravity.

Fig. 87. Indication of the direction of the sun when dancing on the vertical surface of the honeycomb. The left shows the orientation of the wagging dance on the vertical honeycomb with the given position of the feeder.

At the same time, the wagging upward run means that the feeder is located directly from the hive towards the sun; wagging down the run indicates the opposite direction; The run, for example, at an angle of 60 њ to the left of the upward direction indicates that the feeder is to the left at an angle of 60 њ from the direct direction from the hive to the sun, and so on. The fact that newcomers, due to the subtle perception of the direction of gravity, is thus recognized in a dark hive, they then use it at the time of departure in relation to the direction to the sun.

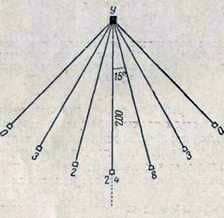

Fig. 88. Results of the “fan” experience. U – hive; K – feeder. Small squares indicate exposed fragrant baits without food. The figures show the number of newcomers who visited them.

Using the same “step experience” method that was used in the study of the distance message, it is possible to determine whether the mobilized bees follow the instructions received regarding the flight in a certain direction. As an example, Fig. 88 shows the result of one such experiment. On the feeder, located 250 meters from the hive, several numbered bees took their food.

The feeder stand had a smell. In 200 meters from the hive at equal distances one from the other, corresponding to the angle of 15 њ, the plates with odor were fan-shaped. The data given show how many newcomers were found during the hour and a half experiment at the observation posts. Only a few of them deviated from the right path.

In the tropics twice a year the sun at noon is at its zenith, that is, it is not in any particular country of the world, and it is impossible to determine the direction to the goal at the location of the sun in relation to the countries of the world. How do bees act in this case? They solved this problem in an amazingly simple way: they stay at home. As soon as the sun approaches the zenith, the bees arrange a lunch break even on those days when the tropical heat at noon is not so great that it is impossible to use the good bribes available in nature.

Only by special intervention can they be caught visiting the trough at these hours, but in that case, returning home, the pickers dance randomly, making a direct run in all directions. This should be expected, and this serves as a confirmation of their ability to navigate the sun.

Surprisingly, it turned out that the angle of 2-3 њ from the zenith is already sufficient to enable bees to determine the direction of the sun and correctly transmit it in the dance. The facetted eyes, fixed motionless on the head capsule and consisting of thousands of slightly inclined individual ocelli, are surprising devices for measuring even such small angles.

Fig. 89. The area at Mount Schafberg, where experience was conducted with the flight of bees around the obstacle; X – the location of the trough. The observation hive stood on the other side of the crest of the rock, about the same height.

In the mountains and winged creatures can not always reach the goal by direct means. What are the bees used to indicate to their comrades a detour to the source of food? In the rocky terrain, in the vicinity of Lake Wolfgangsee, there is a rich choice of possibilities for studying this issue. One day our observation hive was placed on the Schafberg mountain behind the crest of the rock, and the feeder, which was quickly covered with the bees on it, was transferred around the edge of the cliff to the place indicated in Fig. 89 with an asterisk.

Fig. 90. The plan of the area where the experiment was conducted. U – hive with bees; л – feeding trough; the circular path by which the bees flew; direct air way to the trough.

Fig. 90 reproduces the plan of the terrain in which the experiment was conducted, and the distance from the hive to the feeding bowl. The assemblers flew back and forth the roundabout depicted in the drawing as an acute angle, but in the dances they did not indicate the direction in which they were actually flying from the hive; they also did not take into account the other side of the acute angle described by them during the flight – both these directions could mislead their girlfriends.

The wagging run of the dancers showed the direction from the hive to the feeder along an air straight line, over which they never flew. Only so they could correctly send their girlfriends along the hive to the place of bribe. Mobilized bees searched in the indicated direction and, flying over the obstacle, reached the goal. Having become acquainted with the source of the bribe, they also found an easier way around the ridge. The behavior of the indicating bees was quite appropriate. But that, having made a detour, they were able to build a real direction without a protractor, ruler and drawing board – this probably refers to the most amazing miracle of the miracles with which the life of bees is so rich.

Fig. 91. Experience pointing upwards. Well – an observation beehive inside the radio tower. The feeder is mounted on the platform on the top of the tower.

This involuntarily suggested that for each increasingly difficult task the bees necessarily find a solution. And yet one day they did not know how to help themselves. The beehive was behind a rare metal grating of structures, inside the radio tower. The feeder with the help of a winch and a stern attached to the rope was placed on the top of the tower, just above the tap of the native hive. An expression for the concept of “up” bee lexicon is not provided, since in the clouds the flowers do not grow.

The assemblers who visited the top of the tower did not know how to report the direction, and made circular dances that mobilized their girlfriends in search of a bribe on the ground in all directions of the meadow, and none of them found the way to the source of the bribe that is above. When the feeder was transferred to the meadow at a distance corresponding to the height of the tower, the system indicating the direction began to function flawlessly.

A wagging dance with its rectilinear progressive wagering run, as well as a circular dance with its circular runs, apparently with amazing symbolic expressiveness, call for action: one – directing into the distance, and the other – to the searches around the native hive. Thanks to a well-regulated system, those bees that need to fly a long distance get precise directions about the purpose of travel.

But, when hundreds of newcomers mobilize and follow the directions of the dance, among them there are often separate bees that act differently. Some bees, who were present at circular dances, are looking for bribes in the distance, and watching wagging dances – near the hive or in the wrong direction from it. Did they not understand the language of the bees? Or are they stubborn who prefer to choose their own way?

However, after considering the phenomena that gave rise to such an “incorrect” course of action, on the whole it should be concluded that such “originals” can be very useful. If rape blooms somewhere, then it would be good to send a lot of bees out of the beehive there, but it does not stop to find out whether the buds of rapeseed flowers and on the other field did not open at the same time. These originals who do not follow the scheme, we are obliged by the fact that all sources of bribe in the summer zone of the bee family are quickly sought and used.

Как обрабатывать пчел щавелевой кислотой. Как очистить рамки с медом.

Biology of the bee family