The Vikings had no idea of the compass. In distant wanderings across the ocean, they were guided by the sun, moon and stars.

With the orientation you can use the heavenly bodies in two ways, depending on whether it is a short or long journey. Suppose that we have come to stay in a secluded rural house in an unfamiliar area and want to find another house that is a quarter of an hour’s walk from ours, but can not be seen because of the rough uneven terrain. We are shown the direction.

In order not to lose it during our small trip, we must keep the same position in relation to the sun – then we will move in a straight line. This method is often used by animals. It was first observed by some ants. If one of these ants leaves their nest on a reconnaissance journey, it moves at a certain angle to the sun and, therefore, in a straight line. When returning, he perceives the position of the sun as if in a mirror image. The fact that ants really orient themselves on the terrain by the position of celestial bodies can be proved with a simple but convincing experience. If the ant returning to the house is placed in a shade by means of a screen and at the same time from the opposite side a mirror reflecting the sun is set, it immediately starts moving in the opposite direction.

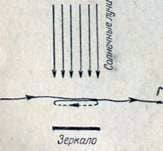

Fig. 66. Experience with a mirror proves that the ants are guided by the sun. The dashed line is the way of the ant when he sees the reflection of the sun in the mirror. D – nest.

For longer trips, it is impossible to use this way of orientation, because the sun, moon and stars change their position above the horizon. If the Vikings did not know that the sun can be seen in the morning in the east, at noon – in the south, and in the evening – in the west, then in the open sea they would swim in a circle. It is truly amazing that bees can also use the sun as a reliable compass, and they pay attention to its position in the sky and simultaneously take into account the time of the day. Although they do not have a watch, they have a sense of time.

The following experience convincingly shows that bees really orient themselves by the sun. We will establish a feeding trough at a point 200 meters away from the observation beehive and we will feed from morning to night with sugar syrup two or three dozen bees of paint marked. The stand, on which the feeder stands, is given a faint smell (eg, lavender oil).

A few days later in the early morning we will transfer the beehive to the terrain with a completely different landscape, many kilometers away from the first one. We establish four identical feeders with syrup, having the smell of lavender, in four points from the beehive to 200 meters to the west, east, north and south. Each of them should have an observer who immediately catches every bee that falls on the bird feeder.

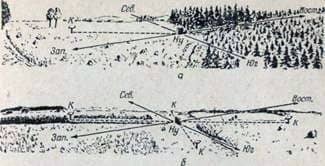

Fig. 67a. The terrain in which the observation beehive was first observed in the experiment with its permutation. View to the east of the feeding table located in the west direction from the hive (K). The hive stands behind trees and houses, a large linden in the middle of the photograph is halfway between the hive and the feeder.

Fig. 67b. The area in which the hive was transferred during the experiment. View from the western aft table (C) to the beehive after its movement. It stands in the middle of a wide meadow, behind two people who are seen in the photo on the right and appear white against the background of a dark forest.

In the new locality, the eye does not find any signs that it could use for the usual definition of the countries of the world (compare Figures 67a and 67b). The hive can not serve as a starting point for this either, because it is oriented now in a completely different way: the ice, turned earlier to the east, now points to the south.

Despite this, quite soon some of the tagged bees appear on the feeding trough, with the vast majority of them coming to the observation post west of the hive, and only a few are mistakenly on other feeders placed in the direction of the other three countries of the world. So, the bees, even in the new terrain for them, were able to navigate the sun, when they flew in the usual direction in search of the already familiar “restaurant”. But during the last flights of bees for a bribe the evening before evening the sun was in the west, and during the last experiment it was in the east. Consequently, bees take into account the time of day.

In order for this experiment to succeed, there is no need to train the bees all day to visit the feeding place. On a beautiful sunny day, we placed an observation beehive on the ground and only at noon we opened the ice. From 3 to 4 o’clock in the afternoon, 42 bees were marked on the feeding trough, located 180 meters north-west of the beehive, which visited the bird feeder until 8 o’clock in the evening.

Fig. 68. Another experience with moving a hive, a is an observation hive (Well) before moving; K – a feeder located 180 meters from the hive; b – observation beehive after moving. Four food tables are placed in the direction of the four countries of the world.

When the next morning this family of bees awoke for new flights, it was remote from the site of its former parking at a distance of 23 kilometers, in a terrain with a completely different landscape, on the shore of the lake. And yet the bees, marked by us and having received the feed on the afternoon before noon, now appeared before the noon on the feeding trolleys: 15 on the western feeder and 2 on the northern and southern feeders. No bee flew to the eastern feeding trough. Most bees appeared early in the morning, between 7 and 8 hours.

So, they did not need to know beforehand that when flying to the western feeding trough, they should keep such a direction that the morning the sun was behind them, and in the evening – in front. They so well feel the position of the sun above the horizon at every hour of the day, that in the morning, when it is quite elsewhere, fly to the feeder in the same direction that they determined by the heavenly compass the previous night.

Is this “knowledge” congenital? Is the orientation on the position of the sun conditioned by the old, numbering millions of years and transmitted by inheritance property of the bee colon? Yes and no.

You can ask the bees themselves about this. If you keep young bees in the basement, where they are deprived of the opportunity to observe the position of the sun, and then bring them into the wild immediately subjected to training and the next day to be moved to another location, then it does not work, because the bees will not be able to find a direction, on which they were trained on the eve. They acquire this ability only after, for many days during flights in the wild they will become acquainted with the daily movement of the sun.

This is a very wise device, because the movement of the sun varies with the time of the year. It is also not the same at different geographical latitudes. Winged creatures can relatively quickly settle around the globe. Therefore, a frozen, hereditary attachment to a scheme suitable only for one place in the world would be unfavorable for them. If you now transport the producers of honey from one part of the globe to another, there will inevitably be a terrible confusion, and the beekeeper should also be pleased that every bee from the first days of life has to get acquainted with the daily movement of the sun in the conditions of this locality.

It is remarkable that small astronomers at the same time discover exceptional talent and stand the next difficult exam. The family of bees is kept until noon in the basement and for many days gets the opportunity to fly in freedom only after noon. Young bees can only observe the afternoon movement of the sun. Then, in an unfamiliar area for them, they also train in the afternoon in one direction, determined by the compass direction, and the next morning they are again transferred to the terrain with an unfamiliar landscape. Bees fly in the direction in which they were trained. They were able to restore the whole of its daily movement over the horizon only by the afternoon shift of the sun.

Since in other life situations the bees do not manifest themselves as such deep thinkers, it is likely that the propensity to perceive this vital training course is inherent in them by nature itself – and in this sense the hereditary transmission from previous generations plays a significant role.

The moon and the sparkling constellations of the night sky, serving as reference points for the Vikings, do not say anything to the bees: at night they remain in the hive. But under the blue daytime sky they surpass the man-navigator, because the eyes of the bees determine the plane of polarization of light.

We already have an idea of how, in the sensitive cells of each individual eye, the bee, due to the action of polarized light, has its own picture of illumination. It is contrasted with fully polarized light, less contrast with partially polarized light, and its distribution varies markedly with the change in the direction of the light oscillations.

Thus, polarized light propagates from the blue sky, the intensity and direction of oscillations of which depend on the position of the sun above the horizon, and for a given position of the sun – from the characteristic features of each section of the sky. This is easily seen if you mount a device with a polaroid so that it can be easily rotated in any direction and rotated at any angle, and then directed to different parts of the sky.

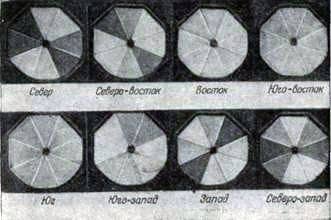

Fig. 69. The polarizer is mounted in a metal frame in such a way that it can be installed in the direction of any part of the world and at any height. The designations of the countries of the world and the angle of deviation are plotted on two semicircles.

Fig. 70. A view of the sky through eight triangles of a polarizer; height above the horizon 45 њ. Photographs were taken on September 25, 1944 at 10 o’clock.

Each of the triangles of the polaroid gives its picture of illumination. Therefore, we can imagine that flying bees perceive light not by a single patch of a complex eye directed directly at the sun, the position of which in this case is constantly but simultaneously thousands of individual eyes, each of which perceives a different picture of illumination, and related to the position of the sun. So they perceive the entire sky with a combination of individual eyes, while simultaneously orienting along it and recording the slightest deviation from the direction of flight a thousandfold.

If the sun is closed by a mountain or other obstacle, a small piece of blue sky is enough for the bees to keep the direction as confidently as if they saw the sun.

This auxiliary “navigation tool” refuses only if the sky is covered with clouds. The light that passed through the clouds, unlike the light of the blue sky, is not polarized. But even if the sun is not hidden by a mountain, bees can perceive the sunlight at such cloudiness, when our eyes already completely do not see it. In this they can be envied by the captains of many aircraft and ships.

The bee, of course, can not perceive thousands of disunited illumination samples, as in a star polarizer, and trace their changes. As in our consciousness, the perceptions emanating from the separate sensitive cells of the retina of both eyes merge into a whole stereoscopic image, and the individual perceptions coming from each element of the bee’s eyes are processed by the bee’s brain into a relatively simple general impression, the quality of which we, of course, we can form representations.

Experiments from which this follows give the first proof of the perception of polarized light by the eyes of bees.

Что такое инверсия сахарозы. Чистка ульев.

Biology of the bee family