A person likes to talk about his “five senses,” although science has long established that, in addition to a sense of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch, there are also some other feelings that correspond to special organs. For example, the organ of balance is located in the middle ear, and microscopically small organs of perception of heat and cold are in the skin. These feelings play a subordinate role in our lives, so they have not gained popularity so far.

However, the five well-known feelings are not equivalent. The one who lost his sight suffered heavy damage; it is enough to spend a few minutes in the company of a blind man to understand how cruelly he is offended by fate. With other people, we can communicate for years and do not notice that they have completely lost the sense of smell – so their life has changed insignificantly in connection with this loss. It is the sense of vision that is fundamental to us. But for many animals this sense has sense of smell. For a dog or a horse, the loss of smell is just as catastrophic as for people’s loss of sight.

For the bee, feelings of sight and smell are of great importance. The first period of her life proceeds in total darkness among the inner buildings of the hive. At this time, her eyes do not help, here along with the touch of all her work sends a rumor. Subsequently, when she becomes a collector, carries out the main activity at will, the sense of vision becomes the leading one. If there was no eye, the bee would be lost at will, because it would not be able to navigate.

The meaning of the smell of flowers.

If you carefully look at the bees collecting honey in a flowering meadow, you can make a wonderful observation: one bee rushes from the flower to the flower of the clover and does not pay attention to other flowers; the other at the same time flies from forget-me-not to forget-me-not, completely ignoring the clover and other plants; the third seemed to specialize only in thyme. Analyzing these facts, it can be established that, as a rule, each working bee collects nectar from flowers of a certain type for many days; biologists say that bees are distinguished by “flower permanence”. This applies, of course, only to individuals, and not to the whole family; when a group of bees collects nectar from a clover, other worker bees from the same hive can choose an unforgettable, thyme or some other flowers for the purpose of their flights.

Flower constancy is beneficial for both bees and plants. For bees – because they, while maintaining fidelity to the flowers of certain plant species, everywhere meet the same working conditions to which they have adapted. Only one who has watched how long the bee, which flew for the first time to a particular flower, probes it with its proboscis until it finds the hidden droplets of nectar, and how cleverly it subsequently achieves the goal, can understand how much time is saved by the flower constancy. But even more important is the behavior of bees for flowers, as this determines their rapid and successful pollination; in addition, the pollen, for example clover, would be completely unsuitable for thyme.

So far, everything is simple and clear. But floral permanence gives cause for reflection. How can bees so confidently look for flowers in a meadow of the same species? By their color? In part, of course, yes, but only different types of flowers are much larger than flower stains. However, each kind of flowers has its own peculiar smell. It could serve as an excellent distinctive and identification mark of the colors of each species, if only bees are able to perceive and orientate on it. How can we know if they are doing this?

Training for the smell.

To ask about this bees, we will take advantage of the technique.. it turned out to be very useful in studying the activity of the sense organs in animals, namely, we apply the method of training. We will put somewhere in the open air a table, and on it a cup of honey. Bees will quickly adapt themselves to collect sweet bribes and carry them to their homes. As with visiting flowers, the same bees will always return to the source of the bribe they have discovered. This allows you to slightly change the conditions of the experiment.

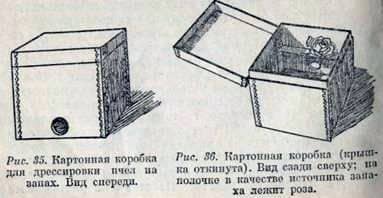

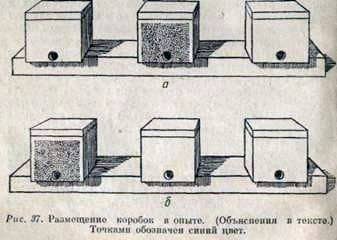

With the help of small amounts of honey, we will teach the bees to fly into a cardboard box with a hinged lid. In the front wall of the box, let’s arrange the lettuce, and inside we will put a feeder with sugar syrup. Now remove the fragrant honey, and on the inner shelf, over the tap, we put a fragrant flower, such as a rose. Next to the box containing the food and rose, we will put several empty boxes without food and without roses. To bees that have an excellent memory in place, do not get used to a certain order of placing items, the box with the feeder will be periodically replaced with one or the other with an empty box. Thus, the smell will remain the only reliable guide to the right place. Will bees learn to use it?

After a few hours you can conduct a decisive experience. We shall expose pure boxes which have no traces of bees, and in appearance and smell absolutely do not differ from each other. In one of them we put a fragrant rose, but we do not put food. Within a few seconds, the behavior of the bees will become completely clear: one by one they fly up to the box of the box with the smell of a rose and enter it, and they do not go into boxes without a smell. Bees perceive the smell of a rose and use it as an identification sign when searching for a source of a bribe.

This does not surprise us. But we can use this method to get a better idea of the smell of the bee. Taking into account the fact of the flower permanence and the existing variety of flower species, let us first of all ask how developed the bees have the ability to distinguish smells. We will set before the bees the task of recognizing among many other different smells the one to which they were trained.

In this case, it would be inappropriate to work with flowers. They smell very strongly, sometimes weakly, and in themselves their smell, after they are broken, sometimes changes in an unforeseen way. In addition, it is not always possible to have the desired set of colors at hand.

In the south of France, an excellent way of preserving the smell of fresh flowers is known: pieces of woolen cloth impregnated with a clean, odorless paraffin oil are sprinkled several times with fresh flowers, for example jasmine; oil absorbs the smell of flowers. Then it is squeezed out of the fabric, bottled and dispatched around the world to produce all kinds of perfume products.

Thus, in a bottle of oil you can get the smell of jasmine, roses, orange blossoms and other plants, and if a few drops of this oil moisten the shelf, placed above the tap in a cardboard box, the latter will be filled with a floral scent of surprising purity. In addition, the perfume industry provides at our disposal a very rich selection of aromatic substances, for example, essential oils.

Now back to our experience. We train bees on the smell of essential oil, which has the aroma of orange crust. We will expose a few dozen clean boxes, supplying this time with each box some kind of smell: one – the smell, which the bees were trained, and others – the smells of various colors and essential oils; none of them have food. How behave bees?

They fly up to the gates of all boxes, as they say, everywhere they stick their noses; flying up to the box with a familiar tasted odor, the bees climb inside and look for the usual food there. Even on the fly they shy away from the tapes, from which other smells spread. And only if the odor coming out of the box, even for our sense of smell, has a great similarity to the training, bees sometimes make mistakes. This happened with two aromatic oils that smell of orange peel. One was received from Spain, and the other from Messina.

For a person with an untrained sense of smell, the smells of these two orange oils are barely discernible. But people, whose profession requires them to exercise and develop the sense of smell, show us what can be achieved by training. When testing two orange oils on the smell of an experienced perfumer for a moment does not doubt their origin. Bees distinguish smells almost as confidently and very little interest in the box with the smell of oil of the Spanish orange. In short, from this and many other experiments it follows that the bees perfectly retain the taste of the smell and with great certainty distinguish it from the smells that are clearly discernible for the human sense of smell. And since in nature there are hardly two kinds of flowers with the same identical smell, the flower constancy of the bees is quite understandable.

The sense of smell of bees can also be tested for the degree of sensitivity: after having inspected the bees for a certain floral scent, they are then offered in a series of successive experiments this smell at increasingly dilute concentrations, until even after the most persistent training the bees are no longer in it is possible to find a box with a smell among other boxes that do not have any smell.

You can conduct a comparative experience with the study of your own sense of smell and thus gain a scale for comparing the “sharpness of smell” bees and humans. Over and above the expectation, a comparison made for all aromatics tested so far reveals a great coincidence. The smell of a bee refuses approximately at the same attenuation, in which it can no longer recognize a person’s sense of smell. Some insects, as well as a dog, a deer and other animals with a “sensitive nose” show very different abilities in this respect.

The degree to which the smell and color affects the bees attending flowers depends, of course, in each individual case on the intensity of the smell of the flower and on the brightness and color of its corolla. But in general, we can say that from afar, the color of the flower serves as a guide for the bees and they are guided by it during the flight to it. However, in the immediate vicinity of the flower, the bees will know by smell whether it is the kind of plant they are looking for.

This can be demonstrated very clearly by one more experiment, if the bees are inspected simultaneously for smell and coloring, and then offer them separately a choice. For example, we fed bees in a blue box that had the scent of jasmine. After a long training we put the blue box on the left without an odor, and on the right – an unpainted box with the smell of jasmine. Returning from their hive, the bees are already coming from a distance to the blue box. However, getting closer to the tap and not feeling the usual scent of jasmine, they suddenly stop in the air, and only a few of them get inside.

Most bees are taken for useless searches and quietly flies around the boxes. Some approach at the same time a few centimeters to the tap, from which the scent of jasmine emanates, and, after a moment’s hesitation, resolutely slip inside the tap, despite the absence of a blue color. The smell is more convincing for them.

This is confirmed by observations in the meadow. Often you can see bees pickers coming up in search of a particular flower to plants with other flowers, the color of which for the eyes of a bee is similar to the coloring of the flowers sought. But, being in the immediate vicinity of the flower and feeling an unfamiliar smell, they are convinced of their mistake, stop for a moment and, not even dropping on the flower, fly away, to where they are attracted by the nearest colored spot.

Where do the bees have a “nose”.

Rarely did science fall into such misconceptions, as it happened in the search for “nose” in insects. It is difficult to understand why this happened? After all, it has long been known that insects, in which the antennae are cut off, do not react to smells. Despite this, many natural scientists tried to find a “nose” in insects on the wings or legs, on the abdomen and on other seemingly unsuitable parts of the body. The fact that insects with severed mustaches cease to react to smells, was explained not by the fact that they lost the ability to perceive the smell, but solely by the heavy damage to the entire body. It was believed that amputation of nerve-rich antennae makes the insect flaccid and phlegmatic.

With two simple experiments you can see how wrong this position is. We feed the bee with sugar syrup in a flat glass cup that stands on gray paper. Around the cup is sprayed a few drops of an aromatic substance, which, for example, has the smell of mint. Put next to two other gray sheets of paper with empty cups and the smell of thyme. So, the bee is trained for the smell of mint. After a while we are convinced that the training was a success. We will expose four blank sheets with empty cups and give one of them a dressing smell (mint), and three others we will add a smell of thyme. The bee searches for food only on a cup that has the smell of mint.

Now repeat the experiment, previously cutting off the bee with both antennae. The operation obviously does not make a big impression on her, because the feeling of pain is almost alien to the insect. She continues in search of the feeder to fly from place to place, lingering over each of them in a vibrating flight. But to detect the smell of mint, the bee is no longer able, and in the end it falls down by chance to this or that cup.

Behavior of the bee does not make impression that she received a serious injury, and it can be proved by repeated experience that because of amputation of antennae the bee does not become either languid or phlegmatic. Feed the bee on a blue sheet and put next to the empty cups on the yellow sheets. Therefore, the training is done in blue. And if we now repeat the previous experience by making amputation of the antennae in the bee, she will, in spite of this, immediately fly to the blue sheet of paper, drop onto it and start looking for food in an empty cup.

Thus, despite amputation of the antennae, she did not lose the ability to react to the surrounding, but only lost the ability to navigate by the smell. Antennae carry the organs of smell.

The organs of smell of bees are arranged differently than ours. In humans, the olfactory organ is located in the depth of the nasal opening, where the innermost nerve fibers penetrate into the tender mucous membrane. Here they are acted upon by aromatic substances that enter the nose together with air when breathing. Insects have no nose. Their respiratory holes (spiracles) are located on the surface of the body and are not adapted to the perception of odors. After all, the organ of smell is one of the important, and sometimes the leading organ of the senses, so it is most appropriate to position it on the front of the head. It is there that the insects have antennae. Inside each antenna there is an olfactory nerve that leaves the brain.

The surface of the antennae, like the surface of the whole body of insects, is covered with a hard chitinous shell, and for the aromatic substances to penetrate the fibers of the olfactory nerve, the entire chitinous covering of the antennae is permeated with the finest canal pores.

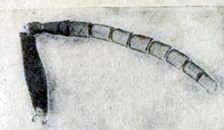

Figure 40 Antenna bee, enlarged approximately 20 times. It consists of 12 movably connected segments.

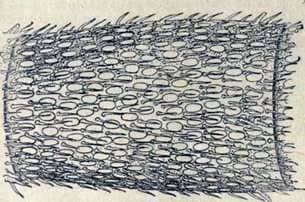

In Fig. 40 shows the appearance of the beekeeper’s beak at twenty-fold magnification, and in Fig. 41-one of antennal segments with an even larger increase. Several elongated light circles are “olfactory pores”. In them, the branching of the olfactory nerve ends. On the outside, they are tightened with extremely delicate film, through which aromatic substances can easily penetrate and irritate the nerve. Between these olfactory pores is a whole forest of the smallest sensitive hairs, so that the beekeeping of the bee is not only the organs of smell, but also the most important organs of touch.

Fig. 41. The segment of the antennae of the bee at very high magnification. Light spots – film-tight pores in the chitinous cover (olfactory organs); between them – numerous tactile hairs.

If you think carefully about it, then the original conclusions come up. With the help of our olfactory nose, it is absolutely impossible to determine whether the smell we perceive comes from a round or angular, short or long object. Odorous substances flow in the vortex of the air stream we breathe, and when they reach the olfactory organ located deep in the nostrils, there is no longer any connection between the shape of the odor-releasing object and the way its odorous substances have reached the olfactory organ.

The bee is different. Since the organs of smell and touch are scattered over the entire surface of the antennae, when in the darkness of the hive she probes and examines with antennas the cells that smell of wax, the egg or larva laid by the uterus, its tactile and olfactory sensations must be in accordance with the shape of the object. The consequence of this is the bee’s ability to “bulk” smell. This can be compared with the “bulk” of our vision and the familiar close ties of visual impressions with a physical, tactile perception.

But if we smell a hexagonal cell of a honeycomb or a wax ball rolled up from it, we get the same impression – it smells of wax. For a bee, perhaps, the “hexagonal smell of wax” is also different from the “round smell of wax”, as for us the kind of wax honeycomb from the kind of wax ball. Organs of smell can achieve due to this great perfection. We can not understand this, because it is alien to our sensations. But in the life of a bee working in the dark and oriented only with the help of touch and smell, the perfection of these senses plays a decisive role.

Tastes differ.

“De gustibus non est disputandum” (there is no dispute about tastes), says the old saying. If two truck farmers can not agree among themselves, which of them has grown larger Cucumbers, their dispute can be resolved by an arbitrator. But, when two people argue about what coffee is more delicious – with sugar or sugar-free, it makes no sense. It is easy to verify by experience that the same taste substance acts differently on different people. It is only natural that everyone considers the best that meets his tastes. No persuasion and decisions of the arbitrator can force him to give up his opinion.

If even among people there is no common opinion in what is tasty and what is tasteless, is it any wonder that the tastes of the insect family quite often differ from ours. Rather, those cases when between us and insects reveal certain features of similarity deserve to be noted.

One of them is to separate the “chemical senses” into smell and taste. The sense of smell due to the extreme sensitivity of the appropriate organ is designed to detect some objects located in the distance. The smallest particles that release volatile aromatic substances are transported through the air and excite the olfactory nerves. The sense of taste is relatively less developed, and its role is limited to checking the chemical composition of food when it is taken. The limited nature of this feeling in bees and in humans is manifested in the insignificance of the number of tastes determined by taste: sweet, sour, bitter, salty.

In the whole kingdom of animals, the evaluation of sweetness is especially common. However, the sharpness of the sense of taste is subject to significant fluctuations. A small fish – a sea cock – is able to taste 100 times more diluted sugar syrup than we do. There are butterflies, in which the sensitivity of the taste organs located at the tips of the feet is more than 1000 times greater than the sensitivity of the human tongue.

To regale is in this, so to say, the meaning of life of bees, because nectar, in essence, is a sugar syrup that bees recognize and collect because of its sweetness. But one who considers bees to be particularly sensitive to the taste of nectar, of course, is mistaken. Quite the opposite: a sugar solution of about 2% concentration, in which we still very distinctly feel the sweetish taste, the bees are not distinguished from simple water. Even bees that perish from hunger do not touch such a solution, although they greedily attack any drop of sugar syrup as soon as they establish what it is.

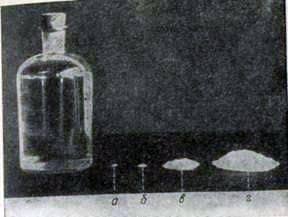

Fig. 42. The bottle contains 1 liter of water. A number of piles of sugar have been piled nearby, which need to be dissolved in water so that the butterfly (a), the fish (sea cock, b), the man (in) and the bee (d) can feel the sweet taste.

To make it more clear, I photographed a bottle containing a liter of water, and next to it – a bunch of sugar, which should be dissolved in this amount of water, so that the sweet taste of the solution could be felt by the butterfly, sea cock, man and bee, known to us by its sensitivity to taste sensations . A butterfly can use the smallest amounts of sugar for its food. The fact that the taste of bees is relatively insensitive to this substance has its own reasons. After all, bees, collecting nectar, harvest food for the winter. When dealing with poorly concentrated, sugar solutions, they would not have achieved success, since these solutions can not be stored.

The hostess will not save sugar when cooking jam, because otherwise it will become moldy – the bee will not put liquid honey in its cells. Nature has created her so impervious to taste, so that she does not even try to act biologically inappropriate. But plants, so to speak, meet the need of bees to have a suitable food for storage. Nectaries of their flowers produce juice with surprisingly high content of sugar (in most cases, from 40 to 70%).

Bees can not be deceived by offering them saccharin or other substitutes that do not have nutritional value, but our taste is so similar to sugar that it is easy to confuse with them. Not because, of course, that bees are smarter than us! The reason is simply that all the substitutes, which seem very sweet to us, are insipid for bees.

To disaccustom the children from the habit of sucking their fingers, they are greased with quinine. He is so bitter to the taste, that this means of education is a preference for all others. Bees with considerable pleasure drink completely inedible for our taste sugar syrup, which is added quinine. Less than we are, bees are sensitive to other bitter substances.

One could list some more “perversions” of their taste. But we are not going to make a cookbook for bees, and so we can limit ourselves to what has been said.

Practical application of scientific research.

Beekeeping is not only an activity for amateurs, but also a very useful thing. Modern cultural forests without hollow trees no longer provide bees with all the necessary living conditions. If a person had not “domesticated” bees, then innumerable centners of precious sugar juice of flowers would be lost in vain or would fall only in the stomachs of flies and butterflies. But even more than honey, the indirect benefit brought by beekeeping is appreciated. The fact is that most of our crop plants are pollinated mainly by bees, without which these plants would give an insignificant harvest of seeds and fruits or would not bear fruit at all.

Beekeepers tend to take so many honey from bee colonies that the food left in the hives for winter is not enough. In return, they feed each family 3-5 kilograms of sugar in the autumn, which is fed to the hive in the form of a syrup. This is beneficial to the beekeeper, because honey is more valuable than sugar. For the needs of beekeeping, it would be better to sell fodder sugar at a lower price. However, the financial authorities express a perfectly understandable desire that this cheaper sugar really benefit the bees, and not because of human weakness used in the household. They would like to appropriately “spoil” it to make it unsuitable for people to feed.

Many ways of denaturing sugar have been proposed, and for some time have been used for this purpose: peat flour, river sand, sawdust and charcoal, pepper and much more. But some of these impurities proved ineffective, because they were easily removed from sugar, others were unprofitable for beekeepers. Therefore, in many countries, to the great regret of beekeepers, the permission to sell special sugar for bees was canceled.

Only an accurate knowledge of the characteristics of the taste of bees can lead to the solution of this old problem. It would be most expedient to use the reduced sensitivity of bees to bitterness. Among the substances tested, there was one that attracted attention because even the slightest trace of it in the product causes a person to feel an excessive, unbearable bitterness. And for bees, it has no taste. From the point of view of chemists, this substance (which is called octoacetyl sucrose) is nothing more than sugar, combined with a small amount of acetic acid.

Parts of the molecules of acetic acid, associated with sugar molecules, make it bitter for humans, but tasteless to bees. Its use as a substance added to sugar has long been inadvisable, since it is difficult to obtain and it is expensive. However, in the end, the efforts of the chemists were crowned with success; they succeeded, on the basis of new methods, to obtain a cheap bitter substance. Its proprietary name is oktosan.

If a very small amount of such a bitter substance is mixed with a large amount of sugar, all the sugar will become unsuitable for consumption. The bees take the syrup prepared from such a sugar as readily as nectar.

The fact that he will not harm neither the bees nor the brood, could be predicted even in advance, and this was confirmed by many years of experience. Oktozan is absolutely harmless for people. This is important because, although fodder sugar should be fed to bees and can not be used for the production of marketable honey, it is impossible to avoid that there are no bitter remnants left in the honeycombs that can get into the product intended for sale. Customers would indignantly reject bitter honey. But oktozan, having got into honey, again splits into its constituent parts – sugar and imperceptible traces of acetic acid, thus losing its bitterness, as if nature itself wanted to create such a substance that would satisfy the requirements of financial bodies and beekeepers in all respects.

База для пчел. Термокамера для обработки пчел.

Biology of the bee family